Today was the first day of my Cyber Security course, and on the first day we were given an assignment. We have to prepare presentations around a given topic, in pairs. My topic is “How much does my phone know about me- what information is stored and where does it go?” I have a tendency to write when I’m thinking, and so this post is to largely act as a brain dump of the subject. When receiving the initial question, my first thought was “do we mean information stored on the phone, or by companies by the phone”. I’ve decided to take the companies track, as most data collection being performed on the phone is by various companies for their benefits.

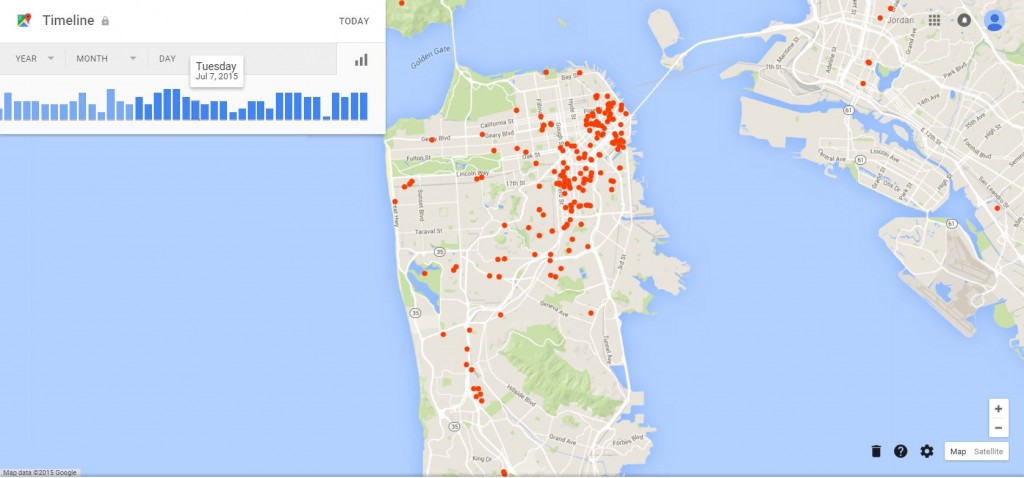

My first thought was to look at Google’s Timeline of mobile app data. I signed in to Timeline with the account I use on my phone, and found that I had location history disabled. I suppose that I did this during set-up as it holds zero data on me. I’ve turned it on now, as I’d like to see what my future maps look like. However, I have previously seen people sharing their maps which are quite complete, and yet they were not aware that Google was collecting their data in this way. An example of how this data can be displayed is seen below, taken from Venture Beat.

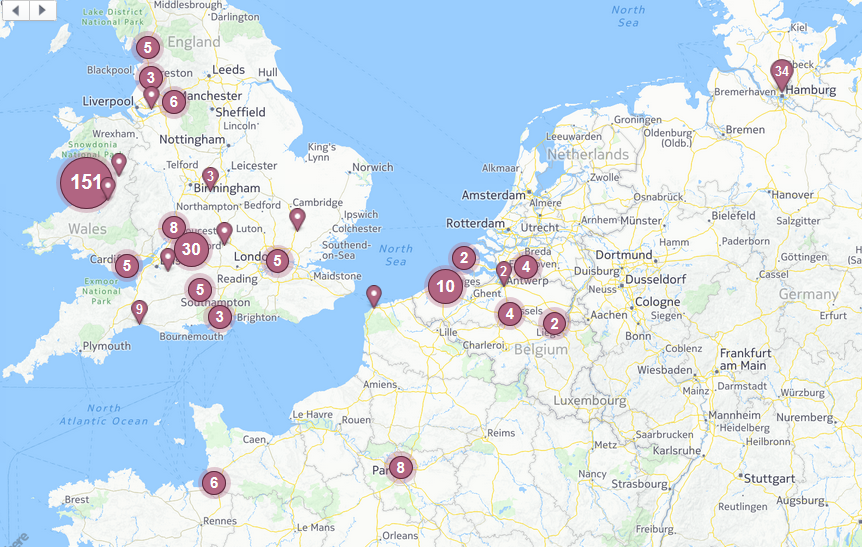

In some ways, location data can be tracked via Facebook, a common use of mobile phones. For this I do have a map which is readily listed on my Facebook profile.

However, I have been entirely aware of the creation of this map. I quite like having the map to “show off”, and so I make an effort to manually “check in” at various locations that I visit. For a previous piece of work, I decided to request the data that is held on me by Facebook. When doing this, I read that the process can be quite tedious (although I am unable to find the guide that I used). From what I recall, Facebook holds something like 50 overarching types of data on users. The official “request your data” form will get you a certain number of these. Sending an email accusing Facebook of withholding data will apparently get you more, and sending a postal request will get you even more. The author of the post I had previously read was of the opinion that it is impossible to get a full copy of your data back. The Facebook help pages list all of the types of data that you may view, with information on how to access it. It seems that some of these are not downloadable easily. I decided to use the “Download a copy of your Facebook data” button on the Facebook Settings page to see what I would get, as I had deleted the results of my previous copy. To request your data be downloadable, your password is required as authentication. A link is then emailed to the address associated with your account, which challenges you for a password before allowing you to download a zip file of the data. The piece of information that I was most interested in is the Security section of the data dump. This contains a list of all active Facebook sessions, and an activity log with entries in the following format:

Session updated

Monday, 5 October 2015 at 17:58 UTC+01

IP Address: 148.88.244.XX

Browser: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; rv:41.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/41.0

Cookie: …RD37

By copy/pasting the IP in to a DB-IP, we can see that this activity comes from the Lancaster University IP pool, which is indeed where I am currently located. It would be quite interesting to have a tool that can pick out IP addresses from a data dump and roughly place locations on a map, but I was unable to find an existing tool that could do so. Perhaps this could make a fun future project for someone!

The implications of this data collection are quite interesting. When I signed in to Google Timeline, I noticed that there was an option to manually add my home and work addresses. It seems odd that Google would need to ask for this, as it seems to be the sort of thing that could be inferred from times (i.e. the place I am at Monday-Friday 9-5 is probably work, whereas the place that I spend nights is probably home). This data could be quite useful to pattern of life analysis, for good or for bad. It could be used to create more context-aware smart devices, such as a work phone that knows to switch off when the user leaves work. It could also allow for some automated location reporting. For example, a spouse could be alerted that the owner has left work, or does not seem to be moving while located on a main road and so is probably stuck in traffic. It does however raise issues of how much do we really want people to know about us. Could a person maliciously use this data to stalk someone, setting up spouse alerts to be informed of their target’s every move? What if the user accidentally leaves their device at work?

My partner in this assignment sent me a link to an article on The Atlantic which attempts to address the question of “What Does Your Phone Know About You?”. In this article, a proprietary digital forensics tool called Lantern is used to analyse the writer’s phone. This tool has pulled out data of very similar types to what I retrieved from Facebook: messages, locations, website visits, emails, photos (with geolocation), temporal behaviors. Lantern provides an interface in which photos/messages are combined with dates/times and locations automatically however, which sounds a bit easier to view than what Facebook had provided me with. I did take a quick look in to the free mobile forensics tools that are available, but none jumped out at me as being something that I wanted to test out. I may make more of an effort to do so in the future however.

The article highlights the use of a tool called the Cellebrite Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED). This is a device targeted at law enforcement officers, which does what it says on the tin. It boasts being able to extract data from nearly 8200 devices (as of 2012, this figure is likely now much higher) devices including phones, PDAs, and tablet computers (among others). The tool can automatically extract, decrypt and analyse the various types of data that may be present on a mobile device in a variety of languages. This can be done by taking a copy of the contents of the file system, or by a physical extraction in the form of a hex dump of the device’s entire storage. The UFED Ultimate can apparently extract user passwords as well as deciphering lock codes. The article proposes a situation in which a person is pulled over for texting while driving, a minor road offense. The user’s device is scanned, and time-stamped images are found of the person smoking drugs earlier that day. The minor texting offense has escalated to one that will likely lead to the user’s arrest. There’s the question of is this is ethically fair. The person certainly should not have been taking drugs and driving, but should the policeman have been able to access such information? To carry out a search, police will have generally have to have a reason to believe that the user is likely to have been committing a crime. Due to how thorough the investigation is using this device, is it overstepping the police’s boundaries to be able to see so much (potentially unnecessary) data about the device’s owner? In my lecture earlier today, the lecturer talked about a situation in which an insurance company buys data from a shop. They are able to see that a person buys copious amounts of cigarettes and alcohol every week, and as a result raise the person’s insurance premiums. Should this be acceptable? I am not an ethicist, and so I am unable to say. The question of how we can and cannot use data is one that is likely to be at the forefront of many minds in the future however.

As previously mentioned, this sort of data can be used to perform some pattern of life analysis on users. However, one of the key ingredients in this is the contents of user images. Image processing technologies have yet to reach the point where the contents of pictures can reliably be categorised, and so this part of analysis would likely require a human operator. Could the apps on a users phone give us more information about a human without requiring a human operator to perform time-consuming analysis? On the Google Play Store on my Android phone, the My Apps tab contains a complete list of all of my currently installed apps, as well as a list containing apps that I have previously had installed and then deleted. I could probably be stereotyped quite well based on my installed apps- Steam, Ingress, AuroraWatch, Fallout Shelter- these suggest that I’m a bit of a nerd. My failed attempts at getting fit could be identified by my Fitocracy and 30 Day Cardio Challenge apps. My socialising habits could be identified by Twitter, Snapchat, Gmail and Tinder. These apps on their own provide a vague picture, but their usage statistics could provide an even greater insight in to my life. My habitual usage of Tinder over a period of time with a near-instant decline in usage suggests that I have found a partner, and provides a rough date of when this occurred. Analysis of data internal to the app could even potentially identify who the partner is. The Ingress app (created by Ninatic, a company owned by Google) provides information on locations that I have been, as well as how long it has taken to travel there (allowing for inference about methods of transportation). This data when combined with data from other users could be used to infer some of my friendship group, as I have groups of people that I will walk around with when playing Ingress. My uninstalled apps list is generally made up of broken/poorly made apps, and so does not reveal too much about me. However, it could be more informative for other people. If someone has deleted an app that aims to help users quit smoking have they recently quit, or have they given up on quitting? A lot of the information that can be collected about users depends on the data security of the companies creating the apps. We’re giving them our data in return for receiving a service. What if a company was to lose our data in a breach, or even to sell our data? I don’t think that any of my data is too sensitive, but it could be of great embaressment to some people, depending on what they use apps for. A HIV clinic accidentally revealed the details of hundreds of patients recently. This can be quite a sensitive topic, and most likely one that sufferers would very much not like to be publicly exposed. What if an app revealed data of this sensitivity? The assumption being made here is that people would provide such sensitive information to an app. I personally believe that they would. The incredibly popular app, Words With Friends, asks for a whole host of permissions upon downloading. Due to the huge popularity of this game, it seems likely that people don’t understand or care what exactly they are agreeing to when they sign up for apps. People provided their personal details to Ashley Madison, and trusted that they were deleted when they asked. People tend to assume that everything will be OK with their data, which for the most part, it is. However, there is the risk of great deals of embarrassment on the part of users if their phone data is compromised, or if the company holding the data releases it through some method.

There is also the financial risk of the loss of a mobile phone. Various banks now have mobile applications, as well as innovations such as PayPal Mobile Payments and the new Apple Pay. If someone was to lose their phone, their financial information could be misused by attackers. The obvious way in which this could be done is through malicious payments from their banking accounts, but there is also the possibility that data on their previous purchases could be collected and sold on as a secondary gain for a hacker. Alternatively, the details could be used to attempt to blackmail the owner of the phone (if, for example, the device had recently been used to make a purchase in a sex shop and the owner was in a very public position that would be harmed by such a revelation). Some mobile data can be collected without even having to physically access a user’s device. An attacker could set up a wireless hotspot in a public location named to appear as though it is safe (such as naming it after McDonald’s’ free Wifi) and wait for users to connect (the connection could be automatic if the user had set their phone to automatically connect to this point, and the attacker masqueraded well enough). They could then use this as a method of gaining access to the device.

In general, I think that mobile devices have the potential to become an extension of ourselves. My previous phone was in theory a smart phone, but behaved much more like a feature phone. I never saw the fuss with owning a smart phone, until I upgraded to my current phone. I now take the phone everywhere with me. I use apps such as Ingress when ever I am walking somewhere, and Facebook when ever I reach my destination. If I’m somewhere interesting I willingly submit an image and my current GPS location to Facebook so that my public map can be updated. I talk to friends about all manner of things via Facebook, and trust that my data won’t be misused. Now I would say that my phone “knows” everything that there is to know about me, and anyone that had full access of it could probably form a very complex and accurate picture of me and my life.

Google already anticipates your home location and work location, telling you the length of time it will take to get to work. It predicts the football scores that I want to see and gives weather forecasts automatically. It also gives me news articles I want to see as well.

Another interesting problem which occurred a few years back is that people were burgling peoples houses based on phone status updates saying said person was at work etc. I believe that this was what prompted phones to have GPS locational data off by default.

My dissertation was reliant on the fact that there was a huge amount of GPS data found in mobile phones. There were a huge amount of studies just into inferring locational information from this data and therefore the habits of the user. My dissertation was about inferring the places a person frequented the least using clustering techniques (its not so easy when there are a ton of data points).

There is also a huge amount of data available in mobile phones anyway as I discovered when I carried out the XRY basic course into mobile forensics.

[…] Google collects various pieces of information on us (I’ve previously written about this here: https://www.vicharkness.co.uk/2015/10/05/thinking-about-how-much-your-phone-knows-about-you/). I decided to have a little dig to try and establish how Google knows that I am reading The […]