Biometric authentication has become a hot topic in recent years. Some people see it as revolutionary to the world of authentication. Others see it as an overhyped security and privacy nightmare. Fuelling this discourse are the large amounts of sometimes misleading information surrounding the reliability of biometrics which can be found online.

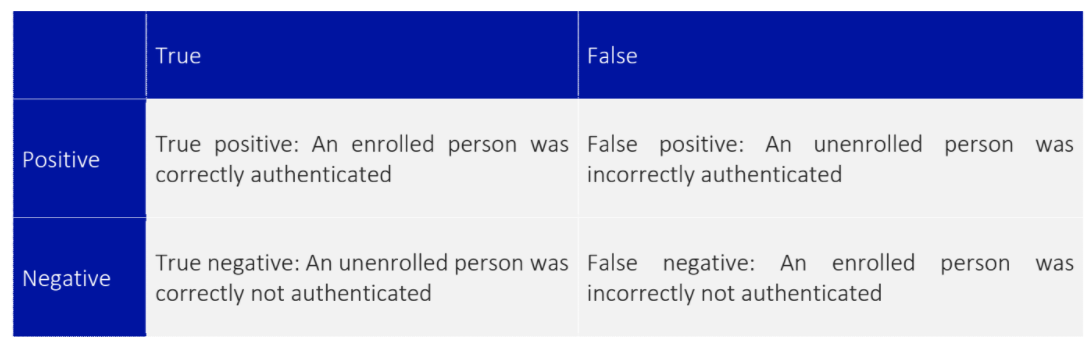

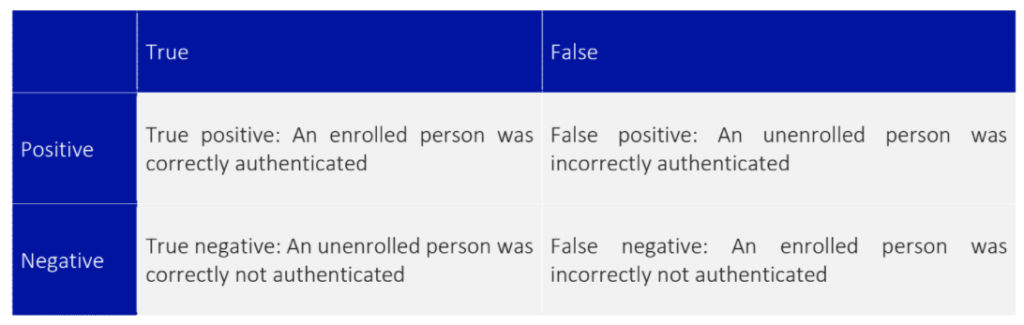

In reality, the reliability of biometric systems often cannot be described with a single value. Imagine you had a computer which stored your most sensitive information, and used facial recognition for access control. You really wouldn’t want the wrong person to be able to gain access to it. When choosing which facial recognition system you want to use, you wouldn’t just care about how good the system is at correctly identifying people with access- you also care about the rate at which the system incorrectly gives access to people. These rates are the “true positive” and “false positive” rates respectively. You may also care about the “true negative” rate, the rate at which an unenrolled person is correctly denied access or even the “false negative” rate, describing the frequency at which a legitimate user is denied access to the system.

Often, significant trade-offs must be made when choosing which of the above factors is the most important to your system. If ease of use is key, then a system with a higher false positive rate may be acceptable so that there’s less risk of users being locked out. An example of such a system may be access control for a hotel lobby. If the door was to not open for a hotel resident (false negative), the hotel may suffer from negative repercussions through visitors having a bad user experience. If the door incorrectly opens for a non-resident (false positive), there likely be much lesser ramifications.

In the previous scenario where sensitive information is being stored, a high false positive rate would be completely unacceptable. It would be preferable to reject enrolled people (false negative) than to risk unenrolled people gaining access to the system (false positive).

Confounding the above problems is a general lack of unbiased testing of biometric authentication systems. Whilst vendors will make claims as to the reliability of their systems, there is no simple way to verify these. In some areas of industry, such as banking, companies must evidence their security claims through third party auditing. No such requirements exist for general biometric products. Unfortunately, the onus is often upon the purchaser to verify the claims being made by the vendor.

What can organisations do to ensure that biometric authentications perform at the standard required? Unfortunately, there is no silver bullet. However, selecting devices from established vendors can be a good first step. Online web searches for products can reveal a wealth of useful information. Sometimes, people working within the cyber security domain will purchase biometric authentication devices to independently investigate their security. The results of these tests can appear in conference talks, blog posts, and in white papers. Sometimes, much simpler reviews can be found. A search on Amazon for biometric locks reveals numerous product reviews where non-technical people have noticed that their system does not perform correctly; a common complaint on cheaper fingerprint readers is that the lock opens for any fingerprint, not just the enrolled one.

If independent information surrounding a product cannot be found online, you may wish to take matters into your own hands. Thankfully, the process required to verify the reliability rates of biometric authentication devices does not require a significant technical background. Simply purchase a single device, and test it yourself. If you are testing a facial recognition system, perform a small test using a subset of company employees (with the consent of employees). Test for low hanging fruit, such as if the system will authenticate a photograph of a person rather than only a real person. Getting employees involved at this stage can also help to build trust in access control systems by allowing them to experiment with the technology to see for themselves how it performs.

Have concerns about introducing real data in to a system that you are unsure is trustworthy? Artificially generated data may be able to help you. Whilst there’s a whole range of other concerns about how easy it has become to synthesise data, it can be great for training and testing other systems. I’ve previously written a blog post about the faces which can be generated using This Person Does Not Exist (blog post here: https://www.vicharkness.co.uk/2019/03/25/this-face-does-not-exist/).

This isn’t limited to the digital world. A product exists called TAPS which consists of fake fingerprint stickers. The idea is that you can enrol these stickers to unlock your phone then stick them to your gloves so that you can still unlock your phone whilst wearing them. But, they are appropriate for use as test data in fingerprint recognition systems.

In general, my advice is to not trust claims being made by vendors. Consider your use cases, and how they could be impacted by the differing true/false positive/negative rates. Find an avenue to verify rates yourself. Ultimately, you are the one that is responsible for the security of your systems and data.

Be First to Comment